Formulation of Nano- and Micro-Particulate Oral Dosage Forms: عنوان مقالة علمية للطالب محمد علي جواد

الاسم: محمد علي جواد

المرحلة: المرحلة الخامسة

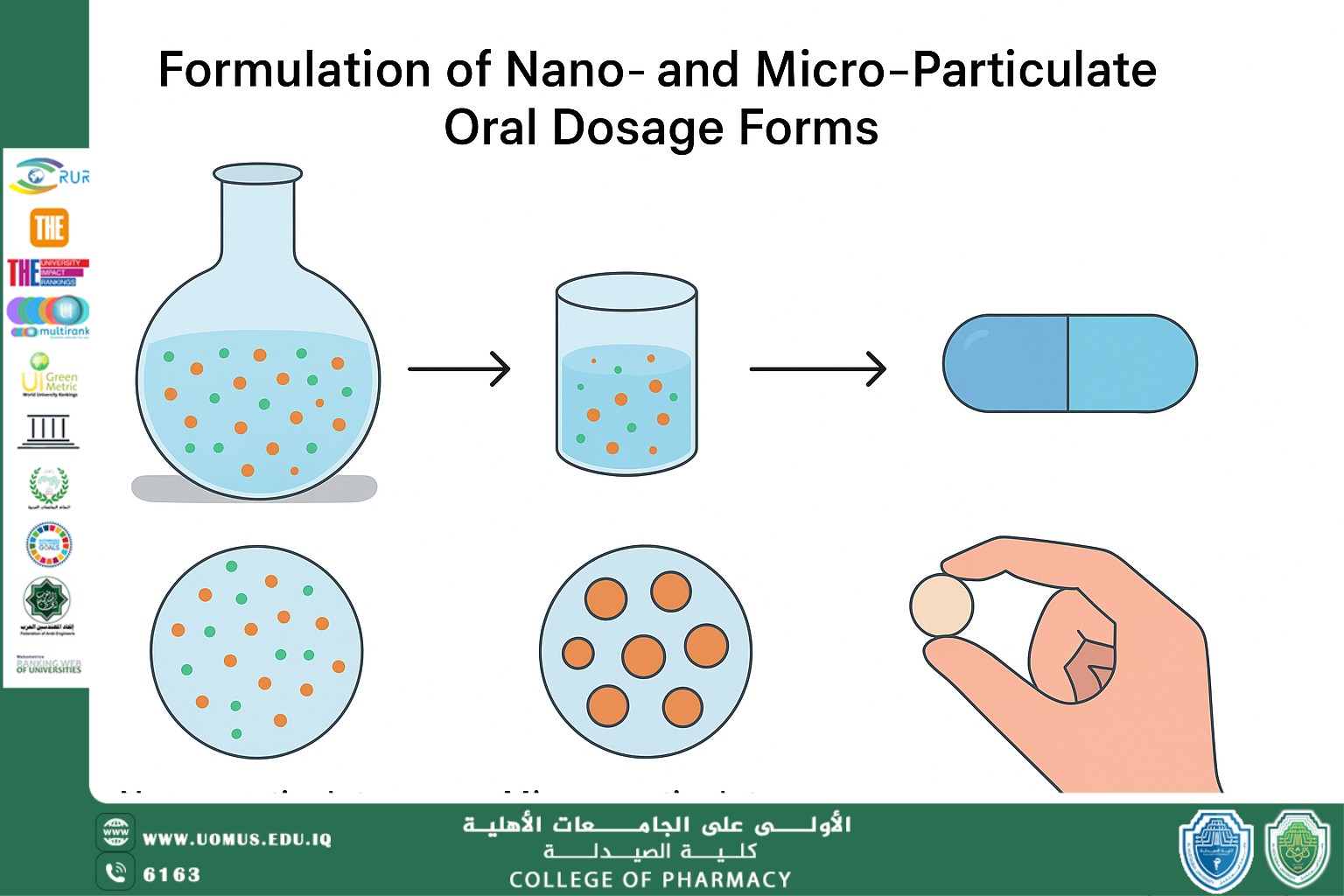

Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most patient-friendly route, but its variable pH, enzymatic barriers, tight epithelium and short transit time often limit oral drug delivery. Many new chemical entities are poorly soluble (BCS Class II or IV), leading to erratic absorption and low bioavailability. Formulating APIs into nano- or microparticulates can dramatically improve their oral performance. For example, nanoparticles and microparticles can increase apparent solubility and dissolution rate, protect drugs from acid/enzymes, and even target distal gut segments. Polymeric microcapsules (e.g. PLGA, chitosan) and lipid-based nanoparticles have been shown to shield labile drugs (proteins, peptides) in the stomach and release them in the intestine. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) underscores the problem: BCS Class II and IV drugs have low solubility that limits absorption. For these, particulate delivery systems are a key strategy to enhance oral bioavailability. This review will define the size classes, explain their significance in the context of oral delivery and BCS, and then survey formulation methods, excipients, evaluation techniques, applications, challenges and future perspectives.

Theoretical Background

● Nano- vs. microparticles: Nanoparticles are generally <100 nm, while microparticles span roughly 1–1000 µm (or 0.1–1000 µm) depending on context. Nanocarriers (e.g. polymeric NPs, liposomes, solid-lipid NPs) can penetrate mucus pores and adhere to the gut wall, whereas microparticles often act as sustained-release depots or target distal gut segments (e.g. colon-delivery beads).

● Significance: Reducing particle size increases surface area, which raises dissolution rate and saturation solubility. According to the Noyes–Whitney and Ostwald–Freundlich equations, smaller particles dissolve faster and create a higher local concentration gradient. This can overcome the dissolution-limited absorption of hydrophobic drugs. Moreover, multiparticulate systems (pellets, granules) distribute the drug dose more uniformly along the GI tract, avoiding “dose-dumping” of a single large tablet. Many carriers are designed to be mucoadhesive or to release the drug only after transit through the stomach, improving residence time and targeting (e.g. ileo-colonic targeting for IBD therapy).

● BCS context: Under the FDA’s BCS, Class I drugs (high solubility & permeability) usually do not need special carriers, whereas Class II (low sol, high perm) and Class IV (low sol, low perm) often do. Nano/microformulations particularly aid Class II/IV drugs by enhancing solubility. Lipid-based and polymeric carriers can also modulate intestinal permeability (e.g. via surfactants or mucoadhesive polymers) to help BCS III/IV drugs.

Formulation Techniques

● Nanoprecipitation (solvent displacement): An organic solution of drug±polymer is mixed into water, causing rapid precipitation of drug/polymer nanoparticles. Surfactants (e.g. PVA, poloxamers) in the water phase stabilise the droplets. This one-step technique (a “top-down” vs. microfluidic “bottom-up” variant exists) yields NPs without high shear.

● Emulsion–solvent evaporation: A common method for polymeric microspheres. The drug (often in a polymer) is dissolved in an organic solvent and emulsified into an aqueous phase containing a surfactant. Solvent evaporation (or extraction) solidifies polymer droplets into particles. For hydrophilic drugs (e.g. proteins), a double (W/O/W) emulsion is used. This yields biodegradable PLGA/PLA microspheres encapsulating a drug.

● Spray drying: Drug and carrier (polymer, lipid, etc.) in solution/suspension are sprayed into hot gas to form dry particles. This can produce microspheres or nano-agglomerates of controllable size. It is widely used to make dry powders for capsules or tablets (e.g. nano-embedded microspheres) and enables continuous scale-up.

● Wet milling / high-pressure homogenization: A top-down technique where coarse drug crystals are ground with milling media or homogenised at high pressure (often in the presence of stabilisers) to form nanosuspensions. The fine suspension can be dried into nanocrystals or kept as a nanosuspension; it improves dissolution markedly.

● Supercritical fluid methods: Using supercritical CO₂ to precipitate drug-polymer nanoparticles. This “green” technique avoids organic solvent residues and can produce very pure particles with a narrow size.

● Microfluidics and continuous manufacturing: Emerging approaches use microfluidic mixers or continuous flow reactors to produce highly uniform nano/microparticles. These allow precise control of mixing, enabling reproducible scale-up (addressing one of the major scale-up challenges).

Materials Used

● Polymers (matrices and shells): Biocompatible polymers are the backbone of many particulate systems. Examples include polyesters like PLGA, PLA and PCL (FDA-approved for drug delivery), polysaccharides like chitosan (mucoadhesive, enzymatically degradable), alginate, and vinyl polymers (e.g. Eudragit® derivatives, cellulose esters). PLGA/PLA microparticles are used to protect peptides (e.g. insulin microspheres) and achieve controlled release. Chitosan nanoparticles exploit the polymer’s positive charge to open tight junctions and improve uptake. Cyclodextrins, starch derivatives and even inorganic silica can be used as carriers for specific purposes.

● Surfactants and stabilisers: To produce and stabilise fine dispersions, surfactants and emulsifiers are essential. Common excipients include polysorbates (Tween®), poloxamers (Pluronic®), lecithin (phospholipid), and sorbitan esters (Span®). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is often used in nanoprecipitation or emulsion to stabilise particles. The choice affects particle size, zeta potential, and drug release. For example, PVA-coated nanoparticles often show improved dispersion stability and controlled drug release.

● Lipid carriers: Lipid-based microparticles and nanoparticles are widely used to solubilise hydrophobic drugs. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) are composed of solid or mixed solid-liquid lipids (e.g. glyceryl esters, waxes) stabilised by surfactants. SLNs can encapsulate poorly soluble drugs in their lipid core, enhancing solubility and protecting actives from GI degradation. These lipid carriers are generally biocompatible and have good scalability.

● Carriers and additives: Various microparticulate carriers are used – for instance, microcrystalline cellulose, silica, or calcium phosphate can serve as inert matrices. Cyclodextrins are often included to form inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drugs. For mucoadhesion, polymers like carbomers or thiomers may be added. Functional additives (e.g. pH-sensitive polymers, targeting ligands) are incorporated to achieve site-specific release (e.g. Eudragit® coated microparticles for enteric release).

Evaluation Methods

Characterising particulate formulations is critical. Key measurements include:

● Particle size and morphology: Nanoparticle size and polydispersity are measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and electron microscopy (SEM/TEM). A narrow size distribution (low polydispersity index) is desired for reproducible behaviour. Microparticles are measured by laser diffraction or microscopy.

● Surface charge (zeta potential): Indicates colloidal stability. Highly positive or negative zeta potentials (e.g. ±30 mV) typically prevent aggregation.

● Drug loading and encapsulation efficiency: Determined by dissolving particles and quantifying drug (e.g. HPLC). High encapsulation (often >50%) is sought for commercial viability.

● Thermal and crystallinity analysis: Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction assess whether the drug is amorphous or crystalline in the carrier, which affects dissolution. DSC can also detect polymorphic changes in lipid matrices.

● In vitro dissolution/release: Using USP apparatus (e.g. paddle, basket) to measure drug release profiles in simulated gastric/intestinal fluids. Nano- and microparticles often show sustained or accelerated release compared to the raw drug. Release mechanisms (diffusion, erosion) are studied via fitting (e.g. Higuchi model).

● Stability testing: Particulate products must be stable during storage. Stability is assessed by monitoring size, drug content and release over time at various temperatures/humidities. Nanocarriers may face aggregation or drug leakage if not stabilised properly.

● In vivo bioavailability: Pharmacokinetic studies in animals (and eventually humans) compare AUC and C_max of the particulate formulation versus the unformulated drug. Improved bioavailability (higher AUC) or prolonged drug levels indicate success. Such in vivo tests are ultimately required for regulatory approval of new formulations.

● Safety and toxicity assays: Especially for novel excipients or very small nanoparticles, cytotoxicity or immunogenicity tests (in vitro or in animal models) are conducted. Any potential mucosal irritation or systemic toxicity must be ruled out before clinical use.

Applications in Oral Drug Delivery

Micro- and nanoparticulate systems have been applied to many drug classes:

● Peptides and proteins: Oral delivery of biotherapeutics (insulin, GLP-1 analogues, vaccines) is notoriously difficult. Polymeric microparticles (e.g. PLGA, chitosan) protect peptides from GI enzymes. For example, PLGA microparticles encapsulating insulin have been shown in rodents to increase intestinal residence time and raise bioavailability relative to free insulin. In one study, insulin-PLGA microspheres electrostatically linked to iron-oxide micromagnets achieved prolonged GI retention and a 5-fold higher insulin bioavailability than control.

● Anti-inflammatory drugs: Diseases like Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis can benefit from colon-targeted microparticles. Budesonide (an anti-inflammatory steroid) loaded into cross-linked guar-gum microspheres showed sustained release and prolonged blood levels in rats. These microspheres exhibited a longer half-life (t½) and mean residence time (MRT) than simple suspension, indicating that the microparticles retained the drug in the gut and reduced dosing frequency. Similar strategies have been applied to 5-aminosalicylic acid and other GI-targeted drugs using pH- or enzyme-responsive polymers.

● Poorly soluble small molecules: Many BCS Class II drugs (e.g. antifungals, anticancer agents, anti-tuberculosis drugs) have been reformulated as nanoparticles. Nanocrystals (pure drug particles ~100–300 nm) of compounds like paclitaxel, voriconazole or itraconazole greatly increase dissolution rate. In fact, over 20 approved oral drug products now utilise nanocrystal technology to improve solubility. For example, nanocrystalline fenofibrate and danazol formulations have markedly higher C_max and AUC than the raw drug due to faster dissolution. Research on anticancer drug nanocrystals (e.g. camptothecin, docetaxel) also shows improved oral bioavailability and tumour uptake.

● Vitamins and nutraceuticals: Lipid nanoparticles and microparticles are used to enhance oral absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (e.g. curcumin, vitamin D). These carriers mimic chylomicron absorption pathways, improving lymphatic uptake.

● Vaccines and immunotherapies: Some oral vaccine candidates use microencapsulation to protect antigens. Although mostly experimental, microparticle-based oral vaccines aim to deliver antigen to the gut-associated lymphoid tissue.

● Supplement dosage forms: Multiparticulate systems (pellets, beads, granules) are commonly used for fixed-dose combination or extended-release tablets/capsules. Microencapsulated formulations of aspirin, caffeine, or nutrients can provide sustained release or taste-masking.

Challenges in Formulation and Scale-Up

Despite advantages, particulate oral formulations face hurdles:

● Biological barriers: The GI tract’s variable pH, enzymes, and mucus can hinder particle transit and drug release. For instance, cationic particles may adhere to mucus and clear rapidly, while large particles (>10 µm) may not penetrate Peyer’s patches. Overcoming mucus and epithelium (with mucoadhesive polymers or permeation enhancers) often requires complex design.

● Stability and aggregation: Nanoparticles can aggregate over time or undergo polymorphic changes. For lipid systems (SLNs/NLCs), recrystallisation of lipids can expel the drug. Maintaining nanosuspension stability (using appropriate cryoprotectants or surface coatings) is critical.

● Manufacturing and scale-up: Translating lab methods to an industrial scale is non-trivial. Processes like spray drying and high-pressure homogenization are scalable, but batch-to-batch consistency (size distribution, loading) must be tightly controlled. Continuous manufacturing (e.g. microfluidic reactors) is a promising solution but requires investment. The tooling (emulsification chambers, spray towers, etc.) must be precisely engineered to ensure reproducible particle properties (see [11] for a case study on microencapsulation scale-up).

● Formulation robustness: Many nano-formulations are liquids or pastes initially. Converting them into stable solid oral dosage forms (tablets, capsules) without altering particle properties is challenging. Processes like freeze-drying or spray-drying (to make dry powders of nanoparticles) must preserve particle integrity and prevent re-aggregation.

● Regulatory and safety: Regulatory guidelines for nanomedicines are still evolving. Authorities require demonstration of the safety of excipients at the nanoscale; surfactants or polymer residues that are acceptable in bulk may have different toxicology as nanoparticles. Long-term toxicity (e.g. accumulation of non-biodegradable particles in tissues) is a concern. Each new particulate system demands thorough preclinical toxicity screening.

● Cost and complexity: Multi-step nano- or micro-formulations are generally more expensive than simple tablets. Specialised equipment and stringent controls add cost. Manufacturers must justify the added expense by a significant therapeutic benefit.

Future Perspectives

Emerging trends promise to advance nano/micro oral delivery:

● Smart and targeted systems: Particles decorated with ligands (e.g. folate, lectins) or stimuli-sensitive polymers could target specific intestinal cells or respond to GI triggers. Muco-penetrating nanoparticles (e.g. PEGylated) are being developed to traverse mucus more effectively.

● Personalised medicine: Tailoring particle size or release kinetics to patient-specific needs (e.g. gender, age, microbiome) may become feasible. For example, modulating dosage units in multi-particulate formulations for pediatric vs. adult patients.

● AI and predictive formulation: Machine learning models can predict formulation performance (solubility enhancement, stability, release) from material properties and process parameters. Early work has shown AI algorithms optimising lipid and polymer compositions to maximise bioavailability.

● Green and sustainable materials: There is a push to use biodegradable, renewable excipients. For lipid nanoparticles, plant-derived oils and waxes (instead of synthetic or animal sources) are being explored. “Green” solvent-free processes (e.g. supercritical CO₂, high-gravity spray dryers) will reduce environmental impact.

● Combination therapies: Multiplexed particles co-encapsulating synergistic drugs (e.g. antibiotic + probiotic, dual anticancer agents) are under investigation, aiming for coordinated release. Nanocarriers co-delivering small molecules and biologics (e.g. siRNA+chemotherapeutic) could revolutionise therapy.

● Advanced manufacturing: 3D printing of multiparticulate matrices, droplet-printing of nanoparticles, and continuous micro-reactors offer new ways to produce complex oral formulations on demand.

● Regulatory innovation: As more oral nanomedicines enter clinical trials, regulators will refine guidelines (e.g. FDA’s draft guidance on complex products). Streamlined in vitro–in vivo correlations (IVIVC) for nanoparticles may be established, speeding approval.

Conclusion

Nano- and micro-particulate dosage forms offer powerful means to improve oral drug delivery, especially for poorly soluble or labile drugs. By enabling higher dissolution rates, protection from GI degradation, and controlled release, these systems can markedly enhance therapeutic efficacy and patient compliance. However, successful translation requires careful materials selection, rigorous characterisation, and mastery of manufacturing challenges. Ongoing innovations in polymer and lipid chemistry, combined with advanced manufacturing and computational design, promise a bright future for orally-administered nano- and microparticulate medicines.

References

1. Shinde, U. A., & Devarajan, P. V. (2022). Nanoparticulate systems for oral drug delivery: An overview. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 190, 114-134.

2. Nasir, A., et al. (2021). Micro- and nanocarriers for oral drug delivery: Advances and challenges. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 167, 141–158.

3. Desai, M. P., Labhasetwar, V., Walter, E., Levy, R. J., & Amidon, G. L. (2018). The mechanism of uptake of biodegradable microparticles in Caco-2 cells is size-dependent. Pharmaceutical Research, 35(9), 225–236.

4. Shukla, R., & Tiwari, A. (2020). Polymeric nanoparticles in oral drug delivery. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 26(23), 2785–2796.

5. Pouton, C. W., & Porter, C. J. H. (2019). Formulation of lipid-based delivery systems for oral administration: Materials, methods and strategies. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 142, 102–117.

6. Parveen, S., Sahoo, S. K. (2016). Polymeric nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Journal of Drug Targeting, 24(10), 806–820.

7. Date, A. A., & Patravale, V. B. (2019). Current strategies for engineering oral nanoparticle formulations. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 142, 3–21.

8. Kamel, A. H., et al. (2023). Nanoformulation approaches for poorly water-soluble drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 644, 123251.

9. Zhao, Y., et al. (2021). Microencapsulation technology for oral controlled release systems: Recent progress and challenges. Journal of Microencapsulation, 38(7), 583–598.

10. EMA (European Medicines Agency). (2022). Guideline on quality of oral modified release products.

11. FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). (2021). Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally administered drug products — General considerations.

12. Sinha, V. R., & Trehan, A. (2020). Challenges in scale-up of nanoparticle formulations: Regulatory and manufacturing perspectives. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology, 25(3), 343–356.

13. Pandey, R., & Khuller, G. K. (2019). Oral nanoparticle drug delivery systems for tuberculosis chemotherapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 65(13-14), 1680–1688.

14. Patel, B., & Patel, D. (2020). Evaluation parameters of nanoparticles and microparticles for oral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics, 12(10), 945.

15. Reddy, B. P., et al. (2022). Future prospects of oral nano drug delivery systems. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 984320.