Art as the Memory of Humanity: Reflections on Art History and the Spirit of Civilization

Art has never been a mere visual luxury, decorative element, or an activity isolated from the conditions of human existence. At its core, art represents one of the most sincere ways through which human beings have sought to understand themselves, confront the world, and leave a trace that transcends time. Therefore, discussing the history of art is not simply a review of styles and movements, but a reflective reading of humanity’s journey in transforming fear into symbols, wonder into form, and existence into meaning.

The earliest artistic expressions did not arise from a pursuit of pure beauty, but from necessity. Primitive humans used art as a means to interpret nature, appease mysterious forces, and affirm their presence in a world they could not fully comprehend. Cave paintings were early symbolic attempts to control reality and a clear indication that humanity sought not only survival, but understanding and expression. Thus began art’s journey as an act of consciousness rather than mere craftsmanship.

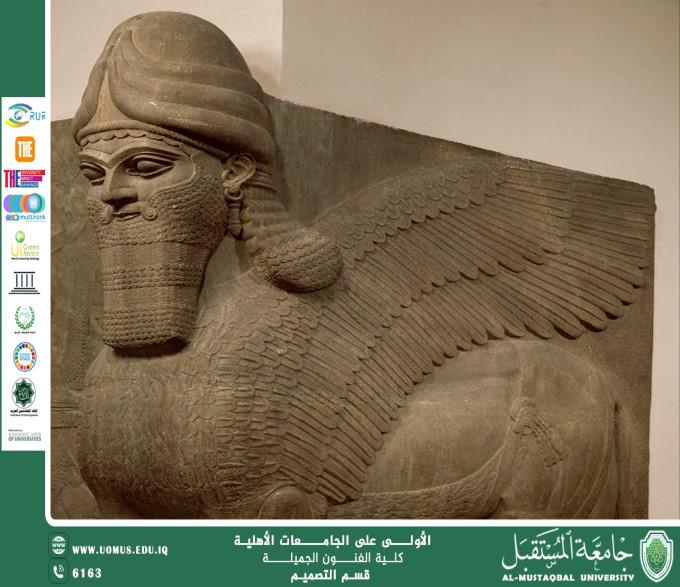

With the rise of civilizations, art acquired greater complexity. In Mesopotamian cultures, art was inseparable from religion, authority, and law. Sculpture, relief, and architecture functioned as tools to establish both cosmic and social order. The rigid formal structure of Mesopotamian art reflects a philosophical worldview that valued stability and repetition as guarantees of continuity.

In ancient Egyptian art, symbolic awareness reached its peak, as artistic production aimed not at capturing fleeting moments, but at achieving immortality. Proportions, poses, and colors were governed by strict systems because art served as a bridge to eternity rather than a mirror of reality, highlighting one of art’s most enduring functions: resistance to mortality.

Greek art marked a fundamental shift in humanity’s perception of itself. The human body became central, while balance, proportion, and movement expressed a belief in humanity as the measure of all things. This celebration of the tangible world was rooted in a deep philosophy that viewed beauty as harmony between reason and nature.

Roman art, in turn, restored art’s political and social function, documenting the empire, embodying power, and recording history. Art became a visual document, a collective memory, and a means of asserting presence across time and space.

During the Middle Ages, the sacred replaced the corporeal, and art became a language of faith, where beauty was measured by spiritual meaning rather than physical proportion. Yet even within this apparent constraint, art continued to express humanity’s existential anxiety.

The Renaissance represented a dual rediscovery of both humanity and art. Reason, perspective, and anatomy returned, infused with a renewed faith in science and experience. The artist emerged as a thinker, and the artwork became the product of knowledge as much as intuition.

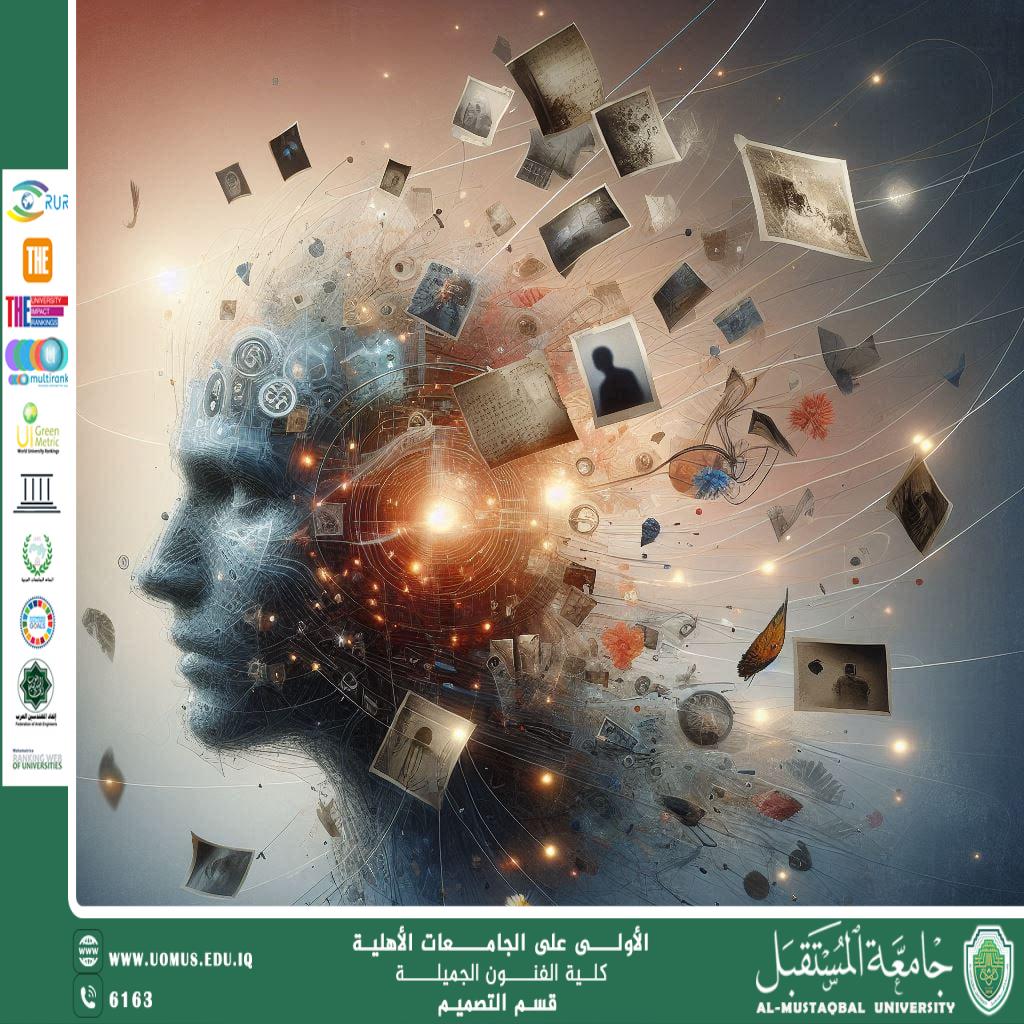

With the advent of the modern era, art underwent a profound transformation. The goal was no longer to represent the world, but to interpret, question, and deconstruct it. Modern artistic movements emerged as intellectual positions before visual styles, each attempting to answer how humanity can live in a world changing faster than it can be understood.

In this context, art became a mirror of crises, alienation, wars, and technological transformations, and the artist a restless witness rather than a mere creator of beauty. Modern and contemporary art thus reflect humanity’s ongoing struggle with the world it has created.

From the perspective of an art history educator, this trajectory should not be approached as a chronological sequence to be memorized, but as an open dialogue between past and present. Teaching art history is not merely about transmitting knowledge, but about cultivating critical awareness, liberating vision, and teaching students how to see before they judge and understand before they categorize.

The essence of art lies not only in the artwork itself, but in the questions it raises and the space it opens between human beings and themselves. Art does not offer ready-made answers, but sustains the capacity to question. Thus, art history is not simply a record of what was, but of who we are and who we might become, a testimony to humanity’s enduring attempt to understand existence through form, color, and symbol.

Almustaqbal University, The First University in Iraq.