Cellular Memory: How Cells Remember Past Exposures Prepared by: Lect. Abbas Hamza Khudhair Department of Biochemistry – College of Science – Al-Mustaqbal University

Although cells do not possess a nervous system or a brain, they are able to retain information about past events and modify their future behavior accordingly. This phenomenon is known as cellular memory and represents a fundamental concept in modern cell biology, immunology, and epigenetics.

Cellular memory refers to the ability of a cell to respond differently to a stimulus based on previous exposure. Even after the original signal has disappeared, the cellular response remains altered for a long period of time, and in some cases, for the lifetime of the cell or its daughter cells.

Molecular Basis of Cellular Memory

Cellular memory is not stored in the DNA sequence itself. Instead, it is encoded through stable molecular and biochemical changes, including:

Persistent activation or repression of signaling proteins

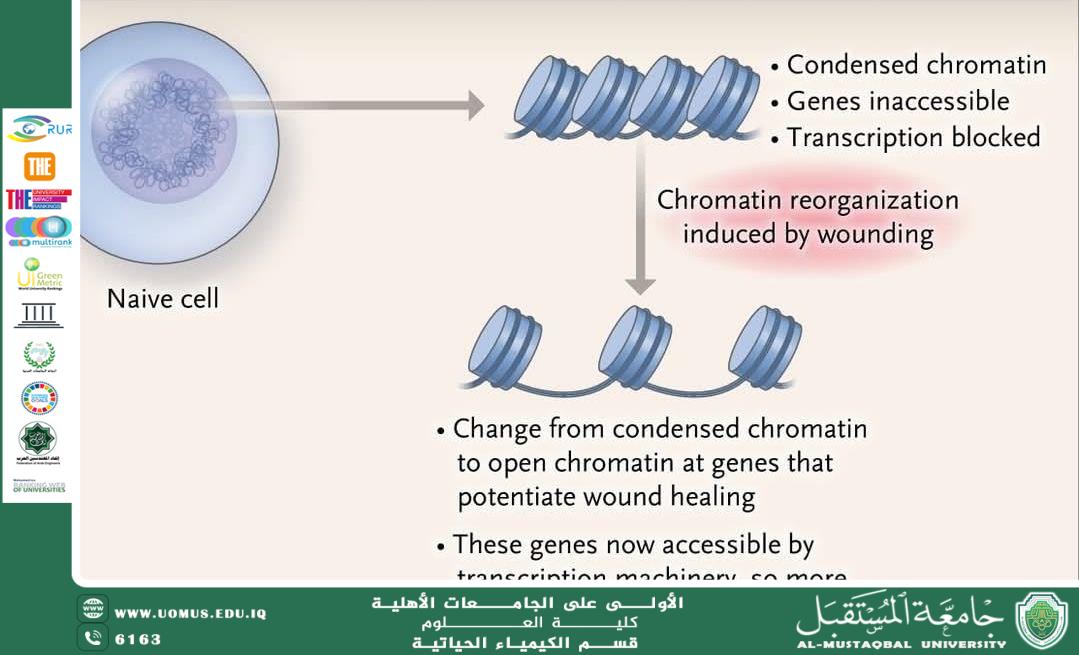

Long-lasting changes in chromatin structure and accessibility

Sustained levels of transcription factors

Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation and histone modifications

Importantly, the DNA sequence does not change; only the way genes are read and regulated is modified.

Biological and Clinical Importance

Cellular memory explains many important biological phenomena, such as:

Why immune cells respond faster and stronger after a second exposure to the same pathogen

How stress, inflammation, or metabolic changes can permanently alter cellular behavior

Why short-term signals can produce long-term biological effects

This concept is central to understanding immune memory, cell differentiation, tissue adaptation, and chronic diseases.

Conclusion

Cells are not reset after every signal. Instead, they carry a molecular history that shapes their future responses. Cellular memory allows organisms to adapt, protect themselves, and maintain long-term functional stability. In biology, life remembers not in minds, but in molecules.