GAMMA CAMMERA

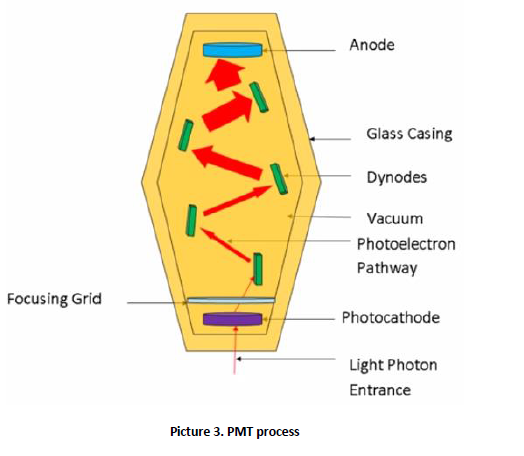

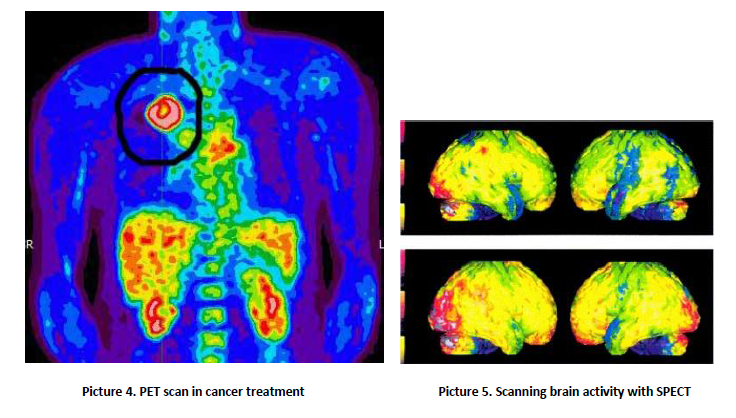

A gamma camera, also called a scintillation camera or Anger camera, is a device used to image gamma radiation emitting radioisotopes, a technique known as scintigraphy. The applications of scintigraphy include early drug development and nuclear medical imaging to view and analyses images of the human body or the distribution of medically injected, inhaled, or ingested radionuclides emitting gamma rays. <br />The emission of a single gamma ray is a very small-scale nuclear phenomenon. It is the role of the gamma-camera head to amplify this microscopic radiation into an electric signal that can be detected and measured. By exploiting a large number of readings of these electric signals, one can determine the map of the radioactive nuclei responsible for the emission of gamma rays. <br />The gamma (or Anger) camera was invented by the American physicist Hal Oscar Anger in Berkeley in 1957. It has since revealed itself to be an irreplaceable tool in a wide range of different diagnoses. Unquestionably the preferred piece of equipment in the field of nuclear medicine, there were 14,000 of them in the world by 1996 and much more now.<br /><br />2. Operation of the device <br />The imaging process begins when a radiopharmaceutical is administered to a patient, usually in one of three ways – ingestion, injection or inhalation. Generally, the injection will be into the elbow or hand (like a blood test), but this may vary according to the test. The delay following the injection is to give the drug time to get to where it needs to go in the body (i.e. lung, bone, kidney, heart). The most commonly used tracer is technetium – 99m, a metastable nuclear isomer chosen for its relatively long half-life of six hours and its ability to be incorporated into variety of molecules in order to target different systems within the body. As it travels through the body and emits radiation, its progress is tracked. <br />Once the patient is injected, they are placed onto the gamma camera bed where they are acquisitioned under the detector for imaging (picture 1).<br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /> A gamma camera detector is composed of a collimator, scintillation crystals, a light guide, photomultiplier tubes (PMT) and preamplifiers (picture 2). The acquisition process begins when the gamma rays emitted from the patient interact with the detector collimator. The collimator consists of a thick sheet of lead, typically 25 to 75 millimeters (1 to 3 in) thick, with thousands of adjacent holes through it. They are used as physical discriminators, only allowing the desired gamma rays to enter the detector. Unlike a lens, as used in visible light cameras, the collimator attenuates most (>99%) of incident photons and thus greatly limits the sensitivity of the camera system. Large amounts of radiation must be present so as to provide enough exposure for the camera system to detect sufficient scintillation dots to form a picture. To achieve the propagation, the collimator septa are composed of lead or tungsten to eliminate any undesirable rays. It is important to ensure no scatter radiation precedes to scintillation crystals, as this can decrease image quality. The thickness and length of septa varies depending on the type of radiopharmaceutical being clinically used.<br /><br /><br /><br /> <br /><br />After the gamma rays have travelled through the collimator, they interact with the cameras scintillation crystals. These crystals are commonly made from sodium iodide (NaI). The crystal thickness should be approximately 13 mm, to ensure image degradation does not occur when the crystals are too thick and to prevent poor detection efficiency of gamma rays caused when the crystals are too thin. Their shape is hexagonal, so they could be positioned to one another, ensuring there are no gaps and all surfaces are covered. <br />Scintillation crystals convert the gamma rays to visible light, which is then directed through a light guide to a photomultiplier tube. The purpose of the light guide is to direct the light to each PMT to increase the efficiency of the light collection and imaging. <br />Photomultiplier tubes, also known as PMTs, are stimulated to produce an electrical current pulse when light signals interact with the photocathode. The photocathode is comprised of a photo emissive substance that expels an electron when hit by a photon. This expelled electron becomes known as a photo electron and passes through a focusing grid which directs it to dynodes. The dynodes are positively charged materials that attract the photoelectron. As the photoelectron moves from dynode to dynode, the electron is multiplied until it reaches the anode. The amount of signal amplification is between 3 to 6 times the initial input for each PMT (picture 3). Preamplifiers are also another way to increase signal output.<br /><br /> <br /><br />Types of devices and applications <br />SPECT and positron emission tomography (PET) form 3-dimensional images, and are therefore classified as separate techniques to scintigraphy, although they also use gamma cameras to detect internal radiation. Scintigraphy is unlike a diagnostic X-ray where external radiation is passed through the body to form an image. <br /> PET scan <br />The positron emission tomography (PET) scan (picture 4) creates computerized images of chemical changes, such as sugar metabolism, that take place in tissue. Typically, the patient is given an injection of a substance that consists of a combination of a sugar and a small amount of radioactively labelled sugar. The radioactive sugar can help in locating a tumor, because cancer cells take up or absorb sugar more avidly than other tissues in the body. <br />After receiving the radioactive sugar, the patient lies still for about 60 minutes while the radioactively labelled sugar circulates throughout the body. If a tumor is present, the radioactive sugar will accumulate in the tumor. The patient then lies on a table, which gradually moves through the PET scanner 6 to 7 times during a 45-60-minute period. The PET scanner is used to detect the distribution of the sugar in the tumor and in the body. By the combined matching of a CT scan with PET images, there is an improved capacity to discriminate normal from abnormal tissues. A computer translates this information into the images that are interpreted by a radiologist. <br />PET scans may play a role in determining whether a mass is cancerous. However, PET scans are more accurate in detecting larger and more aggressive tumors than they are in locating tumors that are smaller than 8 mm and/or less aggressive. They may also detect cancer when other imaging techniques show normal results. PET scans may be helpful in evaluating and staging recurrent disease (cancer that has come back). PET scans are beginning to be used to check if a treatment is working - if a tumor cells are dying and thus using less sugar.<br /><br />SPECT scan<br />Similar to PET, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) uses radioactive tracers and a scanner to record data that a computer constructs into two- or three-dimensional images (picture 5). A small amount of a radioactive drug is injected into a vein and a scanner is used to make detailed images of areas inside the body where the <br />radioactive material is taken up by the cells. SPECT can give information about blood flow to tissues and chemical reactions (metabolism) in the body. In this procedure, antibodies (proteins that recognize and stick to tumor cells) can be linked to a radioactive substance. If a tumor is present, the antibodies will stick to it. Then a SPECT scan can be done to detect the radioactive substance and reveal where the tumor is located. <br />