Ceramic to Metal Joining for Biomedical Applications

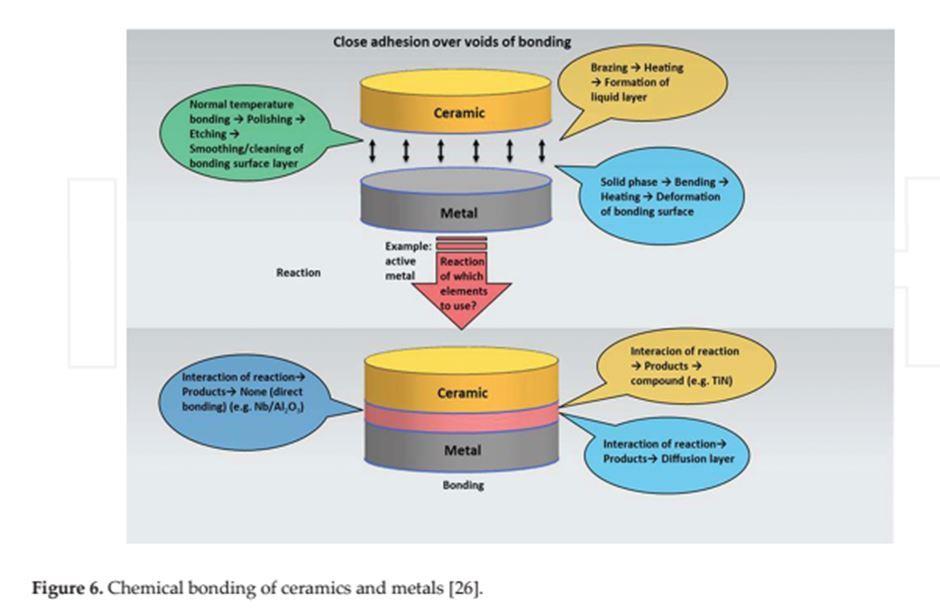

The joining of materials has been used in manufacturing since the beginning of mankind and has become one of the key technologies in many manufacturing industries. The ability to choose which joining process is appropriate at every step is critical in producing highly reliable devices, and the alternatives are diverse though all have advantages and limitations which ever application is targeted. The choice depends upon production economics as well as the mechanical properties desired in the final assembly. These properties go beyond just strength, covering issues such as vibration damping and durability, corrosion or erosion resistance, as well as the ability to correct a defective final assembly.<br /> <br />Even successful joint formation does not guarantee mechanical soundness of the joint. The inherent differences in physical properties between the ceramic and the metal make it very difficult to find an effective process to join that keeps detailed and comprehensive strength and flexibility. There are two primary factors that cause the reliability issue of joint such as the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch and the difference in the nature of the interface bond. The thermal residual stresses are induced in a joint during cooling due to the CTE mismatch and differing mechanical responses of ceramic and metal. This may lead to a detrimental influence on joint strength. There exist many problems between ceramic and metal materials, such as the atom bond . configuration, chemical and physical properties, etc. These problems make the joining of ceramics to metals difficult. The following main problems such as ionic bonds and covalent bonds are characteristic atomic bond configurations of ceramic materials. The peripheral electrons are extremely stable. Using the general joining method of fusion welding to join ceramics with metals is almost impossible, and the molten metal does not generally wet on ceramic surfaces. When there is mass transfer across the interface, bonding is formed by diffusion or chemical reactions. <br />Chemical reactions at the interface lead to the formation of interfacial reaction layers with properties that differ from both the ceramic and the metal . This can have favorable effects on joint quality by increasing the initial wettability of the metal on ceramic surfaces; however, thick reaction layers increase volume mismatch stresses and thermal residual stresses that detrimental to joint strength as shown in figure .<br /> <br />Ceramics exhibit very different thermal expansion behavior compared to metals; hence, considerable residual stress can build up during cooling. This thermal expansion mismatch more or less dictates the use of a ductile filler material. Most commercial brazing systems are therefore silver and copper base. The soft interlayer might not be sufficient to compensate for large differences in thermal expansion coefficients. In such situations, laminated interlayers that provide a continuous gradient thermal expansion coefficient are used.<br />Ceramic-metal brazing: Brazing is a process for joining similar or dissimilar materials using filler metal. The filler metal is heated slightly above its melting point so it flows, but the temperature remains lower than the melting point of the ceramic metal joints. Materials used as fillers for brazing are those that melt above 450 ° C. Flux or an inert atmosphere is utilized to keep two surfaces that have joined and brazing material from oxidation during the heating process. The filler material flows over the base metal and ceramic, and the entire assembly is then cooled to join the pieces together. Brazing forms very strong, permanent joints. Brazing is considered to be well-established commercial processes for ceramic metal joints also , where it is widely used in industry, in different parts, because almost every metallic and ceramic material can be joined by this <br /> <br /><br />