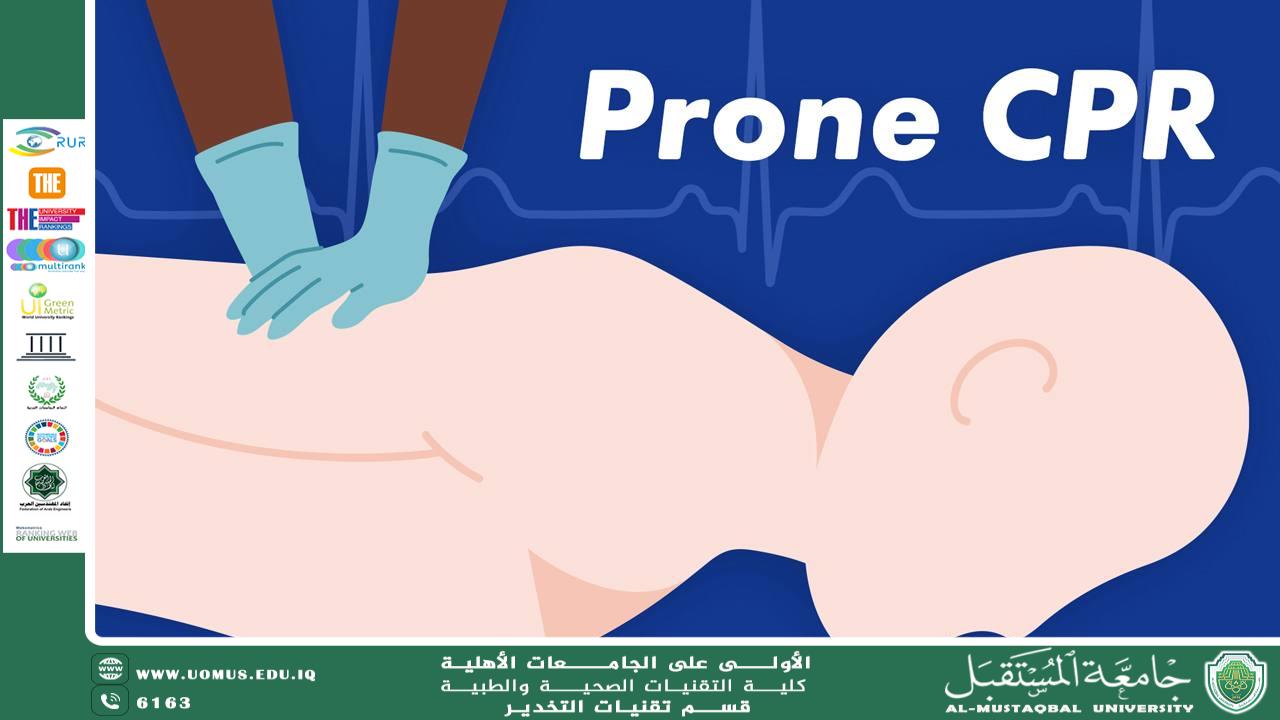

Prone Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (Prone CPR): Concept, Evidence, and Challenges

Introduction:<br /><br />Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is typically performed with the patient lying on their back (supine). However, in certain clinical situations — such as patients positioned prone on mechanical ventilation, during specific surgical procedures, or when it is difficult to turn the patient quickly — prone or reverse CPR may be a practical option to minimize delays in initiating chest compressions.<br />This article aims to review the concept of prone CPR, proposed mechanisms, available evidence, challenges, and future recommendations.<br /><br /><br /><br />Mechanism and Principle:<br /> • Compression site: Compressions are applied over the thoracic vertebrae T7–T10, where the heart is closer to the dorsal wall; a support may be placed under the chest to provide counter-pressure.<br /> • Compression and recoil: Adequate depth and full chest recoil are essential to ensure effective blood return to the heart.<br /> • Ventilation: For mechanically ventilated patients, ventilation can continue without repositioning the patient.<br /> • Defibrillation: Anterior–posterior placement of defibrillator pads is feasible and effective in this position.<br /><br /><br /><br />Available Evidence:<br /> • Mazer et al. (2003): Prone compressions produced higher arterial pressures compared to conventional CPR.<br /> • Systematic reviews (Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2020): Prone CPR is a reasonable alternative when supine positioning is not feasible, provided the patient has a secured airway.<br /> • Clinical reports: Successful partial restoration of circulation has been observed in ICU cases using prone CPR.<br /><br /><br /><br />Potential Benefits:<br /> • Reduces delays in initiating compressions, a critical factor for survival.<br /> • May achieve higher arterial pressures in certain cases.<br /> • Suitable for patients who cannot be moved quickly, especially in severe respiratory failure (ARDS).<br /><br /><br /><br />Challenges and Limitations:<br /> 1. Determining optimal compression depth and site:<br /> • No consensus on the exact vertebral level, though T7–T10 is often suggested.<br /> • Compression efficiency may be lower than supine CPR.<br /> 2. Quality monitoring difficulties:<br /> • Supine CPR allows easy monitoring of depth, rate, and perfusion.<br /> • In prone CPR, evaluation is challenging; monitoring via end-tidal CO₂ or arterial lines may be necessary.<br /> 3. Risk of injury:<br /> • Rib fractures or internal injuries remain possible.<br /> • Detection is more difficult, and improper technique increases risk.<br /> 4. Potential failure in suboptimal conditions:<br /> • Without a secured airway, ventilation is difficult.<br /> • Surgical equipment or spinal hardware may obstruct effective compressions.<br /><br /><br /><br />Discussion and Recommendations:<br /><br />Despite limited evidence, prone CPR is a practical option in emergencies where supine positioning is not possible, but it should not replace conventional CPR when turning the patient is feasible.<br /><br />Future Recommendations:<br /> 1. Conduct randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in simulation and specialized centers before broader clinical application.<br /> 2. Develop sensors or feedback devices to monitor compression depth, rate, and perfusion in the prone position.<br /> 3. Establish clear training protocols covering hand placement, compression force, and monitoring techniques.<br /> 4. Use advanced monitoring (end-tidal CO₂ or arterial lines) when possible to assess effectiveness.<br /> 5. Carefully evaluate risk–benefit in patients with severe respiratory conditions or fragile oxygenation.<br /><br /><br />Conclusion:<br /><br />Prone CPR represents a promising alternative in specific scenarios where conventional CPR cannot be applied. However, the lack of high-quality clinical evidence highlights the need for further research to validate its efficacy and safety, and to establish optimal protocols for clinical practice.<br /><br />Hussein shadad <br /><br />Al-Mustaqbal University <br />The First University in Iraq.