The Emergence of Governance and Its Relationship with Religious Thought in Light of Cuneiform Texts

During the third millennium BCE, the land consisted of several small political units known as city-states. Each city-state was composed of a main city and its surrounding territories, and in some cases a city-state might include more than one city. From time to time, rulers emerged who attempted to unite these city-states into a larger state encompassing all the cities. However, such large states did not last long, and the land would fragment once again.

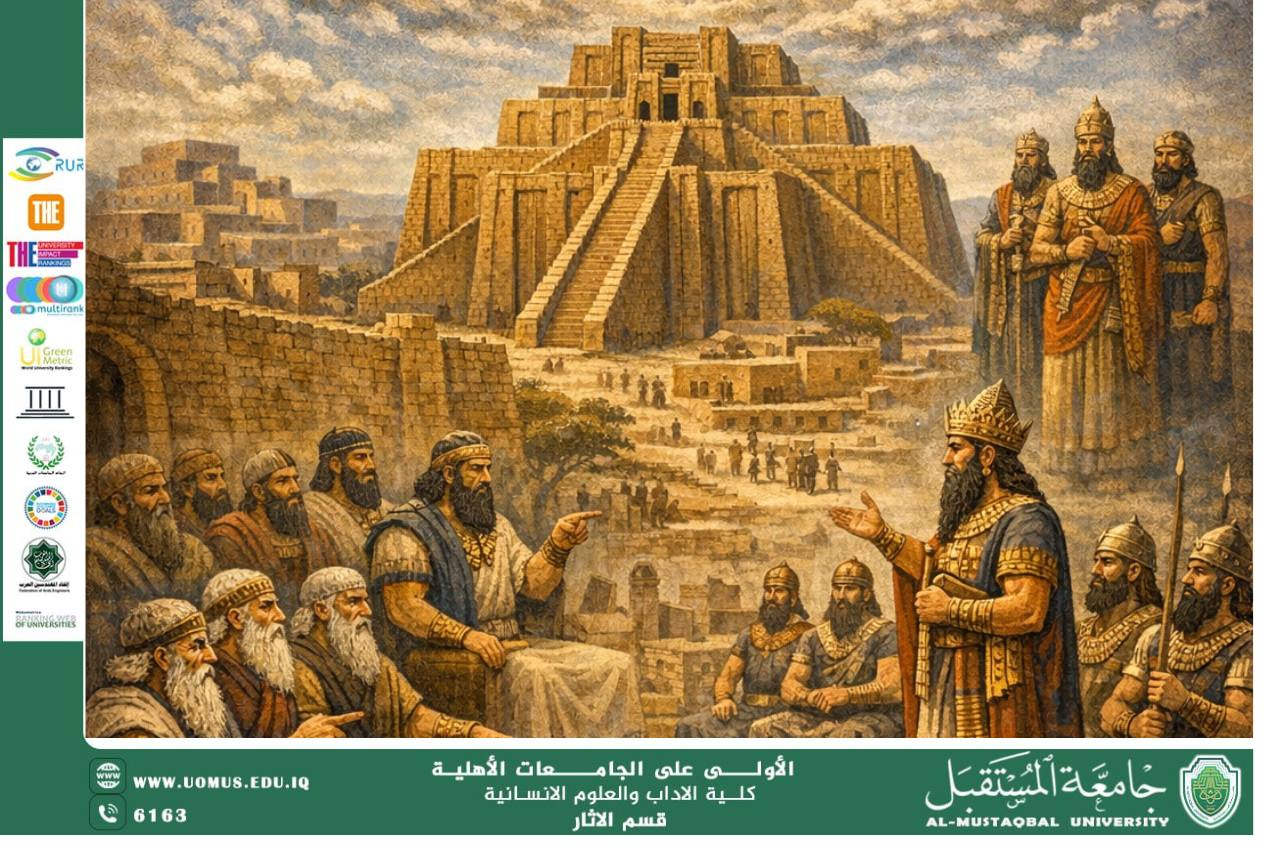

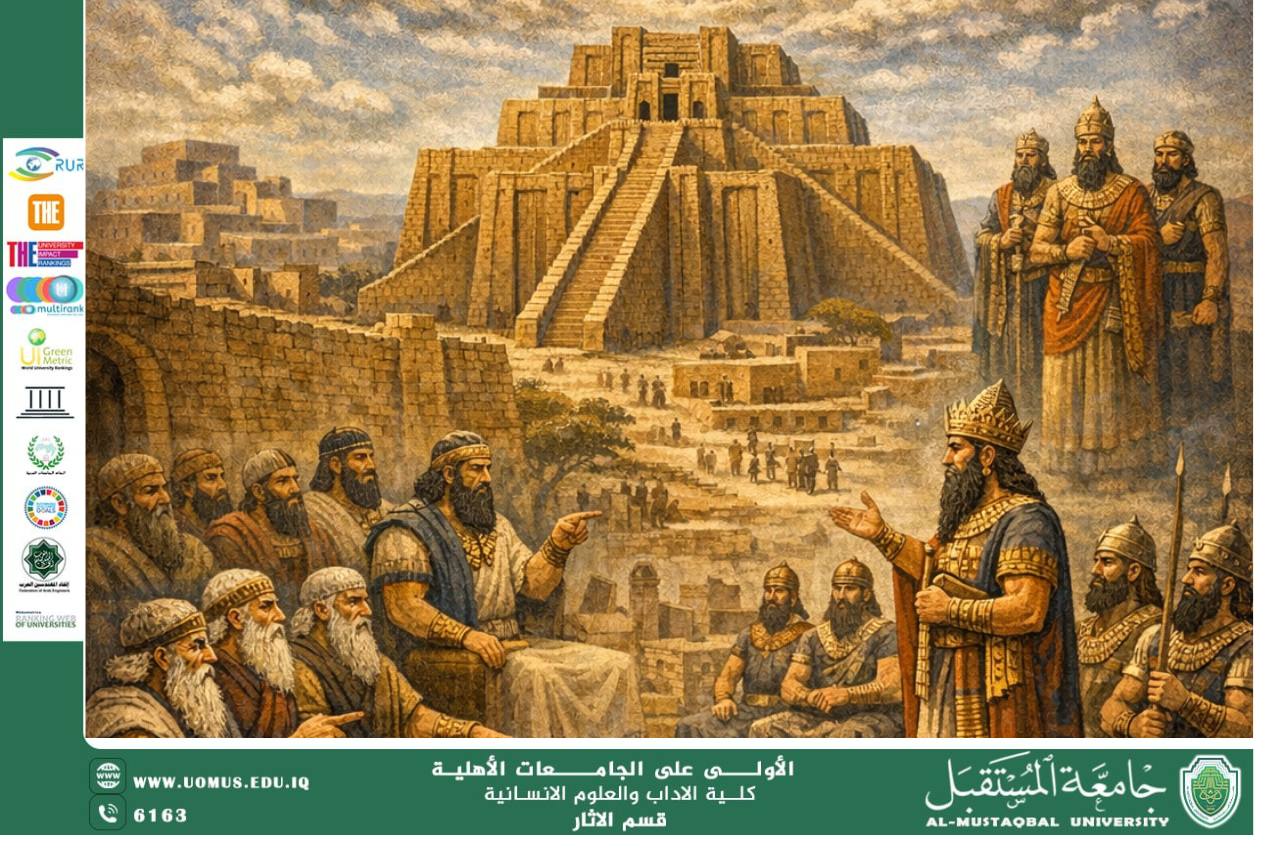

The central place in every city was the temple, which was considered the most important public building and had emerged in Iraq from an early period. The temple represented the center of the city and the محور of its social life. Cuneiform sources indicate that authority was derived from the gods, that rulers and kings were considered deputies or representatives of the deity, and that the temple was regarded as the earthly residence of the god. Despite the important central role of the temple in the city, supreme political power in an early period resided in the person of the secular king. The titles used to designate the office of kingship varied from one city to another, perhaps due to the different ways in which this institution developed.

From cuneiform documents, it can be inferred that the earliest form of “legislative authority” in the city-state was embodied in a council composed of elders and young men bearing arms. This council was convened in times of emergency and crisis to make decisions concerning the city. This is clearly evident in the Sumerian text known as “Gilgamesh and Aga,” which is of great importance because of the valuable information it provides about the nature of the legislative body in the Sumerian city-state and about the nature of conflicts among the early Sumerian city-states.

Some texts show that this council continued to play a role in Sumerian political life from the early periods until the end of Sumerian existence. During the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur, despite the absolute power and authority enjoyed by the kings of this dynasty, the council still played a prominent role in decision-making and in offering counsel. On this basis, some scholars have believed that the earliest form of governance in ancient Iraq was a primitive democracy based on and supported by this council.

Due to the analogical thinking that characterized Sumerian and Babylonian religious thought, this council was considered a reflection of the divine society upon human society. The gods themselves made decisions in their own council, which consisted of fifty gods in addition to the seven gods who decreed destinies. Thus, primitive democracy was the method practiced by the cosmic state in heaven, represented by the divine assembly. Accordingly, the council of the city-state was likened to the council of the gods. The implementation of decisions in the city-state council was in the hands of the ruler, just as in the council of the gods, where the execution of decisions was in the hands of the chief god.

Furthermore, certain aspects of the political and religious structure of the city-states can be inferred from the titles used by their rulers, among which are three Sumerian titles: En, Ensi, and Lugal.